By LEE TSE LING

It was a cold, dark night in suburban Petaling Jaya. Rain lashed the window and lightning streaked shadows on the walls. In the lull between the crashes and grumbles from the sky came a soft rapping at my chamber door. Who could it be?

Certainly not fame, let alone that agent of fame otherwise known as The Publisher. They don’t tend to come a-knocking, as any struggling author will tell you.

Got a killer manuscript though? Why not have a go at publishing it yourself? You might just follow in the footsteps of 19-year-old Christopher Paolini (of Inheritance trilogy fame), Alan and Barbara Pease (Why Men Don’t Listen and Why Women Can’t Read Maps) and James Redfield (the Celestine Prophecy). All of whom landed contracts with publishing colossus Random House at the end of the road less travelled.

Perhaps their talents (I use that term loosely) would not have gone unnoticed by mainstream publishers for long. Maybe self-publishing just catapulted them to a position they would have attained in time anyway. But what about the other authors out there whose sole asset is of the liquid sort?

For up until recently, only professionals dedicated to the business of producing books could afford to run a printing press, and pay their menagerie of: authors, editors, sub-editors, designers, layout artists, proofreaders, typesetters, printers, distributors, marketing and administrative executives (phew).

With such a set-up, small print-runs were too expensive. So publishers printed large runs, which they had to make sure were saleable.

Got a killer manuscript? Why not have a go at publishing it yourself?

This forced them to screen manuscripts with a fine comb.

After all, while writing might be an art, publishing is a business. Every business needs to make money.

But that was before the advent of digital technology and desktop publishing (creating book layouts with computers). Since the late 1980s/early 90s, the status quo between authors and publishers has changed slightly.

Conventional publishers will always hold the lion’s share of the market. But now more people can afford to produce small runs of books for themselves. And such authors – self-publishers – don’t have to brave a gauntlet of scrutiny and approval to do so. But to who’s benefit/detriment is this: theirs or the reading public? For if money buys the last word, what watchdog is left to guard the final product?

Are all self-published books self-serving and self-indulgent? What function does self-publishing fulfil? Is it something to be proud of, as a fast-track way to catch the eye of publishers? Or a last ditch resort taken when publisher after publisher has rejected your manuscript?

“I don’t doubt that there are good writers struggling to get published, but I don’t think we can blame publishing houses for rejecting a majority of manuscripts. Their role to filter out gratuitous writing and to publish works that appeal to the larger audience is very important,” says one freelance book reviewer.

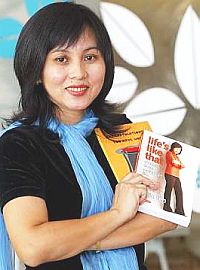

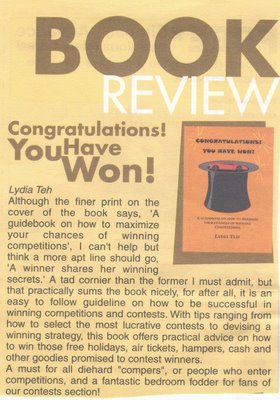

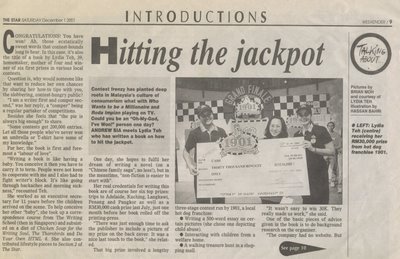

Lydia Teh, a local freelance writer, advocates going with convention for the serious author.

“Personally, I would stick with the publishers. I feel it’s important to get the input of a third party who’s objective because it gives us more credibility,” she says.

Teh’s collection of short articles, Life’s Like That, was published by Pelanduk Publications published last year. Tony Lacey, publishing director of Viking UK, Penguin’s most diverse publishing arm, is more direct.

“Self-published books hardly figure in the stores at all. I don’t think it is snobbery; the fact is, most self-published books are not very good. Otherwise they would be picked up by the many mainstream publishers.

“They can be therapeutic for the author, and admired by his family, but that doesn’t make them good or saleable,” he says.

On the flipside, there are authors who take pride in self-publishing. “If I can do it on my own, I don’t see why I should go to a (conventional) publisher. I know what I want; I know what the book should be,” said Datin Anna Lim. Lim, who recently released her self-published memoirs Beauty & Beyond: The Journey of a Beauty Queen.

Georgianna Das is another local author who took the self-publishing plunge with The Goddess Within in 2004. She initially approached a regional publisher, but deemed their terms unrealistic.

“I would have had to come up with quite a lot of money up front (an advance) for printing etc. and sign a lot of my rights over,’’ she says. “I felt I would be losing as an author.”

From a publisher’s view, Das’ self-enrichment book could be considered too personal and a high risk. Hence the advance as a financial guarantee. However, Das’ first edition of 1,000 books has since sold out, and she is in the process of producing a second edition of 5,000. So it would seem she hasn’t done that badly.

“If you want to pay me, fine, I’ll take a risk. (But) why should I pay somebody to boss me around? I am not going to fight a publishing system that is not mature,” she says.

Which reminds us that publishers, or reviewers within publishing houses, are human. As such, their judgements are not infallible.

“A publisher might think there’s a market for a book, but only time will tell whether it will sell or not,” cautions Teh.

Indeed, Lacey concedes that there are exceptions to publishing convention when it comes to the genre of non-fiction.

“There are a myriad niche markets with highly specialised authors. The individual guru is a romantic concept, and the self-publisher can build on that,” he says.

British publishing authority Jonathon Clifford has this sensible piece of parting advice for would-be self-publishers:

“You must look on the whole process of publishing not as money to make a return, but as money spent on a pleasurable hobby ... providing you with well-manufactured copies of your book.

“If you do also manage to make a small profit, then that should be looked upon as a bonus!”

And if you’re still worried about bookstores being flooded by indiscriminate rubbish (much in the same way the Internet has been flooded by rubbish blogs because of a similar lack of screening), take comfort in bookstore democracy.

One book reviewer put it thus, “I don’t really care whether a book is self-published or not, as long as the content itself is good. I think most people would consider the writer first, then whether the book appeals to them."

The pros and cons of self-publishing

Pros:

• You’re in control of the book; it can be whatever you want it to be. Datin Anna Lim’s Beauty & Beyond: “ I love this concept where it’s not a book you read, look at the pictures and you’re finished with it. To me it’s like a life story, a coffee table book, but a collector’s item as well.” Indeed, “you don’t have to be a young aspiring beauty queen to read the book”, but it would be “good if you were, and wanted to understand what a beauty queen’s life is like”.

• Lydia Teh: “You work at your own pace; with a publisher, you need to have lots of patience. Publishing houses have their own schedules drawn out, and lots of other titles ahead of yours. The basic time frame from acceptance to rolling off the press (locally) is one year to one and a half years.”

• You might catch the eye of mainstream publishers; Georgianna Das claims she has requests to ghostwrite other books following the production of The Goddess Within.

• You can set your own price. Lim’s B&B for example, is going for RM99.

Lim: “I think RM99 is a price most people can afford. It’s less than RM100, I spent so much time and effort on it, and it’s quite good quality.

“I think it’s quite fair, and not too much for a young lady who really wants to buy the book.”

Having said that, leading regional distributor Pansing says authors should generally expect a lot less than half the sale price of the book after factoring in the bookstore’s cut and discounts, distributors cuts, transportation, etc.

• You can dictate where your books go. Das: “Local publishers’ distribution channels are not fantastic. There are so many local books I don’t see when I go to bookshops overseas. I don’t want my book to get stuck and be caught in an agreement where you can’t do any distribution myself.”

• You keep all your revenue; standard royalty payments at Pelanduk Publishing are set at about 10%. Local publishers do not offer advances but they do review unsolicited manuscripts. Viking UK, a division of Penguin UK, typically offers advances that vary from £1,000 to £1mil, and royalties between 7.5% and 10%.

Cons:

• Lim: “You have to oversee the whole project yourself; it’s so hands-on. If you’re a self-publisher, a lot of time and effort has to be spent if you want to do a really good book. If someone else does it for you, you can just hand it to them.”

• As such, you need the right contacts. Das: “I know some of the top editors in town, I had a very good photographer and graphic designer. You have to think about whether you have these resources.”

• Teh: “The biggest headache is distribution; no matter how good your book is. If it’s not in the bookshop then everything is futile.”

• Das: You have to be in a place or business where you know you can push the book (Das runs her own training academy); if you’re not confident about how the book is going to do or how to sell the book, you shouldn’t take this route. It’s a risky one.

• Tony Lacey: “You’re taking all the financial risk with no income upfront. Fundamentally, writers should reserve their energies for writing! Do they really want to spend their time worrying about stock control, distribution, etc?”

How much are we talking about here? Das’ outlay for her first run of 1,000 copies was in the region of RM50,000, supported by revenue from her business. Lim’s ran up to RM200,000, most of which came from corporate sponsors.

• You won’t get the validation / credibility, call it brand name recognition if you like, that comes with being accepted by a respected publisher. Leading regional distribution group Pansing feels that while an author might have what he thinks is a good book, a publisher would be able to decide if it will be successful in the general market.

• And while Pansing won’t turn them down cold, they feel publishers with small portfolios are not economically viable.

An irreducible amount of expenditure is incurred in any interaction between a publisher and distributor. The more books the publisher has to sell, the more worthwhile they are to talk to. A distributor can’t afford to have too many expensive conversations.

• For the same reason, bookstores do not generally deal directly with authors. Renee Koh, marketing manager of MPH Sdn Bhd: “Where we can, we always try to help local authors who self publish. Even so, they need to go through a distributor first to ensure their books are ‘taken care of’.”

“There is a definite future for e-books (electronic version of books) as it is slowly entering the lives of Malaysians today,” said Shoba, the author of Prodigal Child.

“There is a definite future for e-books (electronic version of books) as it is slowly entering the lives of Malaysians today,” said Shoba, the author of Prodigal Child.